A holistic approach to continuous improvement

Paul Brauss shares the toolbox for continuous improvement

Each business improvement methodology has a primary focus and approach to driving improvement in an organization. A process engineer I worked with a couple of weeks ago

asked which of the three improvement methodologies I liked the best between lean manufacturing, the theory of constraints and Six Sigma. This person was seeking advice on the best medicine for his company’s mediocre financial performance. It is not the first time I have heard the question, and I offer this insight for leaders on the verge of making a commitment to improvement and looking to jump-start programs that are now inactive.

Waste and drivers

Lean manufacturing alone focuses on the elimination of process waste. Our lean training traditionally lists seven types of waste with three driving contributors.

The seven types of waste are:

1. Correction

2. Overproduction

3. Movement of Material

4. Motion

5. Waiting

6. Inventory

7. Processing

And the three driving contributors are:

1. Unevenness

2. Overburden

3. Current process methods

Waste has a distinct look and feel, requiring extra floor space, extra time, inventory stockpiles, missed shipments, mediocre quality and an organization that needs to be more proactive in prevention.

The worst of the waste elements is overproduction because it drives unnecessary work with movement, storage and cash drain. Because the waste is visual on the production floor, many lean initiatives focus on shop floor practices with a heavy emphasis on kaizen projects. The commitment to lean real-life practices produces good results. Still, after initial kaizen campaigns around 5S and some basic requirements, they become nothing more than isolated islands of excellence. Efforts are operator focused and typically do not address company culture, so most initiatives run their course quickly without sustained internalization.

The Six Sigma method focuses on process variability. Variation of process drives waste. Understanding process capability and both upper and lower limits are fundamental. Seeing a process drift through regimented quality checks allows time for operators to make necessary adjustments. The principles of Six Sigma focus on customer needs for quality and then eliminate variations to that quality expectation. There is a heavy emphasis on training and certification, and certified leaders tend to direct lengthy projects.

The approach requires a constant focus on data integrity, and operators need a higher ownership level for adoption. Projects are driven by experts within the company who help make a process flow smoother. Since a high level of expertise is required, cultural adoption takes longer.

The theory of constraints hones in on the elimination of bottlenecks. The best book on the topic is ‘The Goal,’ and it’s a mandatory reading requirement for most operational management programs. It is a staple requirement on any continuous improvement reading list. The fundamental requirement is to find the limiting factor in a series of processes. The emphasis is to improve the process until it is no longer a constraint. Then move to the following constraint and repeat. In the converter world, the most logical example is to look at the press and the related finishing equipment partnered with the press. It does not matter how fast you print a label if you cannot perform the finishing processes simultaneously. A mismatch causes inventory bottlenecks and waste. Finding process constraints takes careful analysis and emphasizes a need for trained material flow experts who look for larger high-value targets that will unlock process capacity.

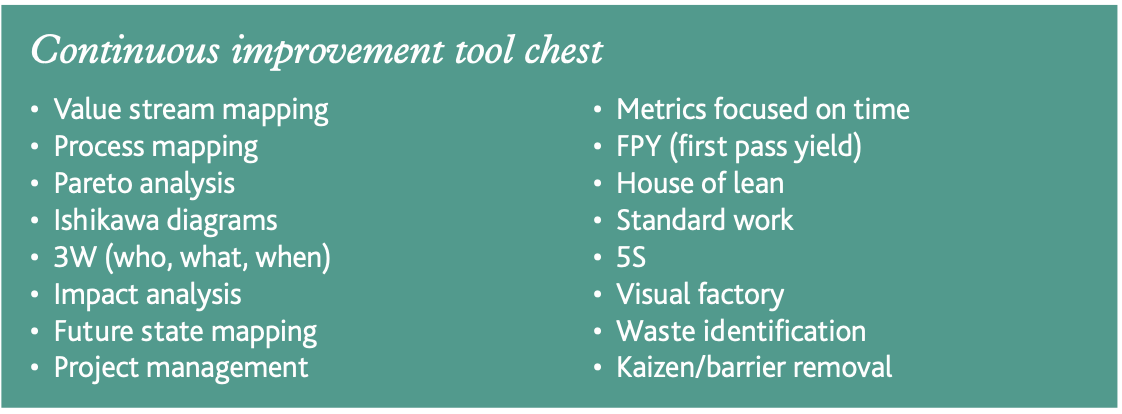

Continuous improvement tools

Continuous improvement tools, such as value stream and process mapping, impact analysis, waste identification and more (see boxout) are essential to the commitment to continuous improvement but, by themselves, cannot address the organization’s full range of strategic needs.

I used most of the tools in the tool chest for many years, first as an industrial engineer, plant manager, and eventually the CEO of a major Fortune 500 company. The game changed when I was introduced to an improvement bundling approach that began with the fundamental belief that an enterprise is a series of linked processes.

Any improvement approach must understand their interdependencies so that performance improvement initiatives have a lasting impact aligned throughout an organization. Governance that reaches all major business processes must be important to a company improvement model, beginning with a high-level strategy implemented over the entire value chain.

Most individualized tools mistakenly seen as large-scale process improvement efforts miss the whole value chain participation requirement and then come up short of expectations, often failing within the first 12 months of implementation.

As our initiatives mature, we understand eliminating barriers on press with improvements such as speed, set-up reduction,

and minimizing change over time are necessary improvements that make work life for an operator much more manageable and produce beneficial results. Companies that have matured enough to understand that process shortcuts lead to downstream issues understand the need to implement barrier removal actions

that help standardize the process. They often move to improve attention to metrics with process audits encouraging elimination and standardization of process variations. Resolving process barriers requires reaching across function responsibilities and implementing changes upstream of the shop floor. The benefit to this activity is often 10 times that of simple process techniques barriers.

There is a way to use all the process improvement tools already in use by many converters and accelerate cultural changes that yield returns 100 times more beneficial than taking the individual approaches discussed.

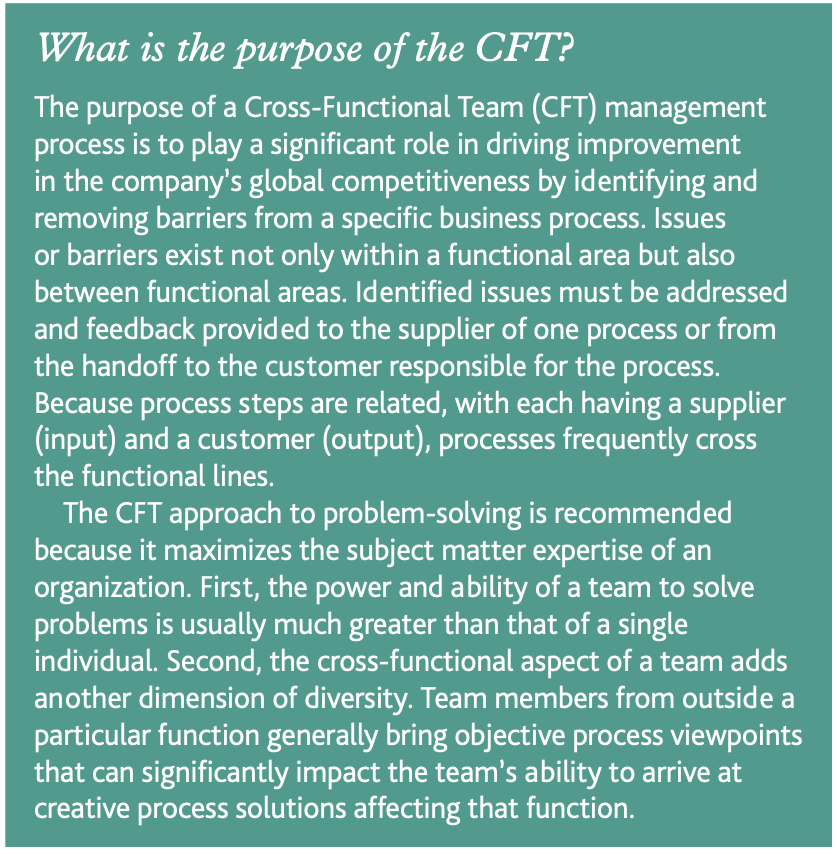

The focus is a Process Value Management approach using inclusive cross-functional teams driven from the top but highly dependent on a bottom-up implementation approach. It requires a holistic view of the organization across all the business processes.

The reason this is unique is that, unlike the singularly focused strategies that address specific areas, the cross-function teams, in concert with the tools from lean, Six Sigma, and the theory of constraints, accelerate a cultural change that brings a new way of acting and thinking to the continuous improvement process.

Cross-functional approach

As competitive forces increase and resource constraints strangle improvement efforts, business owners and leaders search for an approach to challenge leadership to act much differently to address the threats and awaken current resource participation. Using cross- functional teams expands stakeholders’ representation in business improvement decisions. The team prioritizes initiatives, resources and objectives. They do this quickly by staying true to a hierarchy of metrics classified as ‘drivers.’

I was introduced to the process by Dr Phillip Thomas, founder

of the Thomas Group. The cross-functional approach became a holistic organizational catalyst for step changes in performance, eliminating my frustration at the benefit limits of traditional functional methods to improve. Companies that adopted the leveraged system achieved lead time reductions of 45 percent and productivity gains of +30 percent in the first year. The holistic approach assures that improvements in one company area do not have unintended consequences in another area. Before using cross-functional teams, people report suffering through this phenomenon quite often. The best example was working through silos of engineering quick-to-process cost reduction designs and sales quick-to-process orders that were not completely defined and subject to interpretation. The shortcuts upstream required to show the financial results of bookings and cost reduction often led to manufacturing problems.

The implementation approach of process management transcends the functional silo approach and engages more people as subject matter experts. Tailoring the implementation of cross- functional techniques can be achieved for every size organization. The commitment to process focus with driving metrics is universal. The results celebrated by leadership teams who have committed to enhancing their culture through the cross- functional process continue to grow.

Employees recognize the benefits quickly because they participate in a holistic approach to excellence. They advance learning swiftly and become very active in success. Additionally, they become appreciative of their newfound converter partner. The improvement is no longer limited to pockets of the organization.

The cross-functional approach to management provides an overreaching umbrella for change management, enhancing the value chain throughout the organization. The process, including suppliers, helps fortify relationships with the converters and customers that benefit from the improvements.

The leadership team is at the epicenter of success, and their involvement is reflected in the activity of the cross-functional team. They take a complete enterprise view and become the champions for change, amplifying the top-down-driven and bottom-up implementation. The result of this conviction is the change in alignment from conventional silos.

The newly created horizontally linked value chain drives planning, leadership, communication and buy-in at all levels of the organization and all points along the value chain. If an organization has mobilized any activity in the lean initiatives, fitting the CFT structure around this effort will revitalize efforts and perpetuate work. In a visual factory with daily production boards and SQDIP boards (safety, quality, delivery, interruptions, productivity), the CFT leaders walk GEMBA to validate the ongoing efforts and aid operators and office workers in reporting progress.

Paul Brauss, former CEO of Mark Andy and a past board member of TLMI, is a consultant and executive coach. See Braussconsulting.com, and buy his book at amzn.to/2NFzXkB

Stay up to date

Subscribe to the free Label News newsletter and receive the latest content every week. We'll never share your email address.