Wisconsin-based Inland drives growth in label markets

The converter, well-known for its cut-and-stack beer labels, has been branching out into pressure-sensitive, shrink sleeve and other labels.

Mark Glendenning with his sons, Brad and Trent

Inland produces tens of billions of labels a year, making it one of the largest label converters in North America and one of the few of that size that’s still family-owned.

Headquartered in La Crosse, Wisconsin, Inland employs 400 people across six facilities. The company is known for manufacturing cut-and-stack labels for major beer brands, which has regularly earned them Supplier of the Year awards.

But that’s not all it does. Over the past decade, Inland has been diversifying its portfolio, adding flexo, digital, and hybrid equipment to its fleet of gravure and offset machinery, and producing a wider range of label types.

Inland aims to offer customers a high level of technical expertise, an extensive range of products, and a dedication to building relationships.

‘In our business, relationships are still key,’ says Scott Roob, Inland’s chief operating officer. ‘Our customers today, between trying to find labor and everyone wearing 10 hats, they need to make sure that the person they’re talking to, they can trust wholeheartedly.’

History

Today, Inland is run by CEO Mark Glendenning, who is the third generation of his family to lead the company. His grandfather, John Glendenning, started Inland in 1944 as a commercial printer of forms and booklets, primarily for the automotive industry. When he retired, John’s son and Mark’s father, Jack Glendenning, took over.

Under Jack’s leadership, the company entered the cut-and-stack label business by becoming a supplier for a major beer brand in the late 1970s. Over time, Inland added other beer companies to its customer base, transforming the company from a commercial printer into a cut-and-stack label converter.

“Our customers today, between trying to find labor and everyone wearing 10 hats, they need to make sure that the person they’re talking to, they can trust wholeheartedly”

Mark joined the company in 1988, first working in Chicago as a sales representative for Inland. He moved his growing family to La Crosse in 1992 and has run the business from the Wisconsin town ever since. Under Mark’s leadership, Inland expanded even further. In 2015, Inland began acquiring companies to manufacture more types of labels, including pressure-sensitive labels.

The fourth generation of Glendennings is now also involved with the business, with Mark’s sons Trent and Brad serving in engineering and sales positions, respectively.

When it came to talking to his kids about working in the business, Mark Glendenning didn’t insist on his sons working at Inland. He suggested they work elsewhere first, similar to his career path. They could eventually apply for jobs at Inland, but it would be up to their manager to hire them. They would not be getting recommendations from their father. And that’s what they did.

‘Family’ is an important word at Inland, Mark Glendenning says.

‘I get to work with my family all day long, and then go home to my other family, and it’s just the way I want to do business,’ he says. ‘I don’t want to do it any other way.’

The Glendenning family also has a foundation, started by Jack, through which the Glendennings give back to the community by supporting organizations such as the local United Way and YMCA. The foundation also donated a manufacturing exhibit to the Children’s Museum of La Crosse.

Facilities

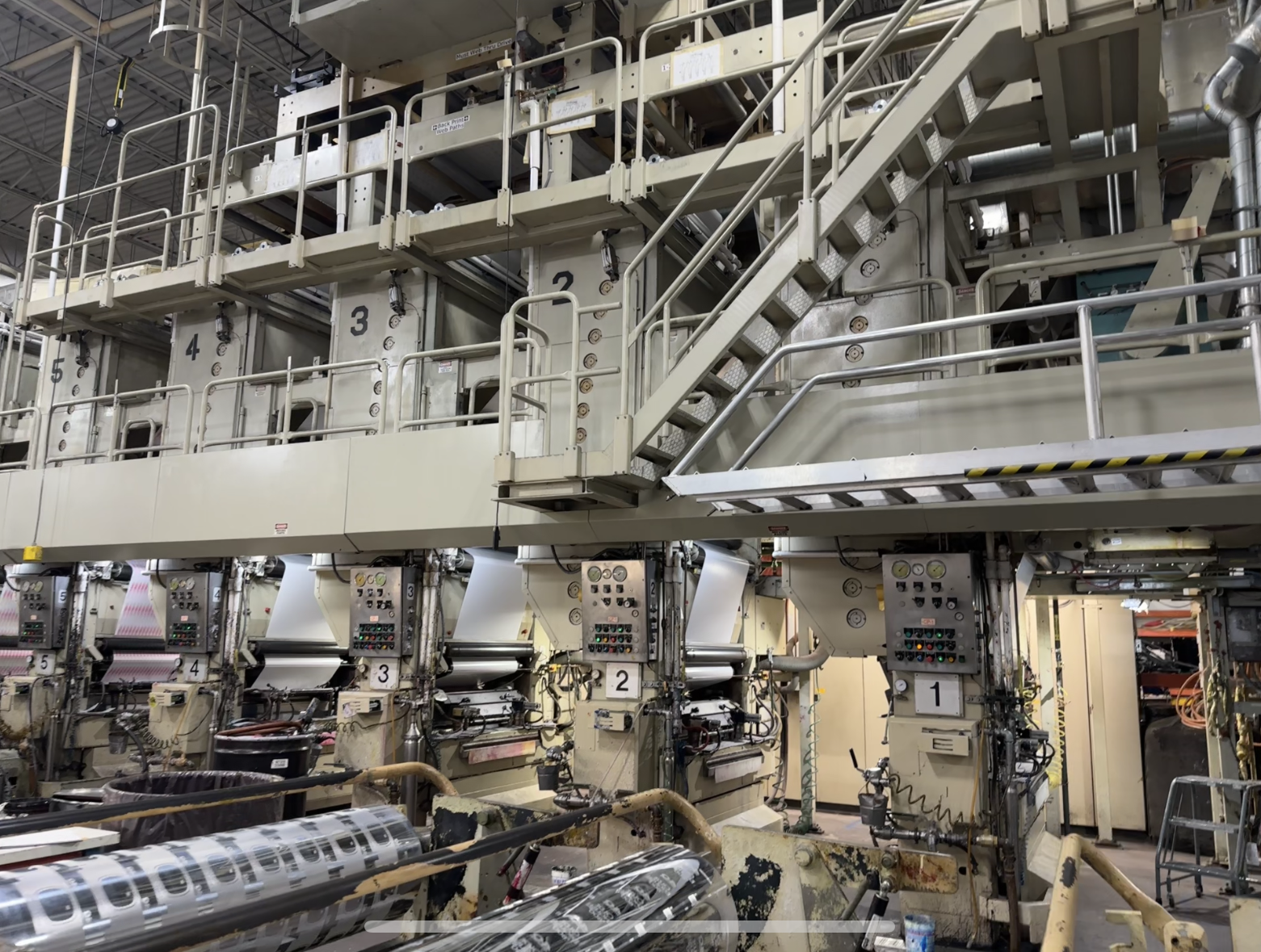

Inland has six facilities across Wisconsin and Pennsylvania: two for cut and stack; one for in-mold labels; one for digital flexible packaging; and the last two for pressure-sensitive, shrink sleeve and flexible packaging.

The three facilities in La Crosse, Wisconsin, produce cut-and-stack and in-mold labels.

In 2015 and 2016, Inland acquired factories in Neenah, Wisconsin, and in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, adding shrink sleeve, flexible packaging and pressure-sensitive labels to its portfolio.

Inland added these other facilities in order to diversify. It is also beneficial for Inland to offer customers a wide range of products.

‘If you’re just a one-trick pony, it’s tough these days to continue to grow,’ Roob says.

Technology

Inland’s biggest growth areas are in its flexo and digital technology, with pressure-sensitive labels, shrink sleeves and flexible packaging.

Inland produces labels primarily for the food and beverage industries, but the company also serves the home care and health and beauty industries, as well as other areas like cannabis and pet food.

Inland continually invests back into the company with its newest press being added in 2023.

Cut-and-stack

Across the industry, wet-glue labels, another term for cut-and-stack, are primarily printed on sheet-fed offset presses.

The paper glue-applied label market is expected to reach 19.7bn USD by 2030, with a CAGR of 4.5 percent year over year from 2013, according to Consultancy Research and Markets.

“We’ve got to continue to take non-value-added processes out. We’ve got to continue to get quicker, get our waste down”

As previously reported by L&L, offset press speeds have increased over the past decade, with machines capable of printing up to 22,000 sheets per hour. Automation has also improved, and more printing steps are carried out in-line than in the past.

The cut-and-stack market is the second-biggest label market for prime labels, after pressure-sensitive, Roob notes. To make a profit in it, though, converters have to produce large volumes of labels, and it’s hard for smaller companies to break into, as the equipment is expensive.

In addition, over the years, the cut-and-stack market has been experiencing a slight decline in volume, even as the value of cut-and-stack labels has increased due to the Covid-19 disruption, mill closures and other factors.

This has led to some converters leaving the space, opening up more opportunities for Inland in the cut-and-stack market.

Cut-and-stack machinery also requires more real estate than pressure-sensitive does, creating another barrier to entry.

Compared to pressure-sensitive labels, cut-and-stack labels also make less waste, as they don’t require a release liner, produce less matrix and only need a small amount of adhesive.

‘From a sustainability standpoint, there’s just nothing more sustainable than a cut-and-stack label,’ Glendenning says. ‘I call it the original linerless.’

Innovative strategies

Like many other manufacturers, Inland has faced workforce challenges in recent years. The company had difficulty recruiting for entry-level positions.

To tackle this, Inland now offers employees diverse shift options and has increased its number of part-time workers. In addition, Inland has implemented a more robust training program. Employees are also cross-trained across different equipment, which enables more scheduling flexibility.

Another challenge Inland faces is that cut-and-stack labels are a lower-cost item compared to many other kinds of labels. However, that just drives Inland to innovate.

‘We’ve got to continue to take non-value-added processes out,’ Roob says. ‘We’ve got to continue to get quicker, get our waste down.’

This has spurred automation at Inland. At its La Crosse facilities, new investments are focused on increasing automation. The company has installed machines that can do automatic jogging, cutting and sorting, inspections, and quality control.

‘A lot of the automation that has been put in does some part of the process, but it also does some validations, inspections and confirmations,’ says Tricia Sime, Inland’s director of innovation, compliance and sustainability. ‘When you have humans doing processes, we just know that there can be inconsistencies.’

Inland plans to continue to add automation.

‘We’re going to continue to try to take the less desirable jobs and automate them and then take those people and give them more rewarding jobs, whether it’s working with robotics or another position,’ Roob concludes.

Stay up to date

Subscribe to the free Label News newsletter and receive the latest content every week. We'll never share your email address.