New look for craft beer

Maneuvering around the materials shortage and supply chain disruptions is an all-too-common practice that practically every industry has been dealing with for the past year and a half.

In the craft brewing business, blank, unprinted aluminum cans have been increasingly difficult to acquire, leaving some brewers without any cans at all and other with an excess that were previously labeled for batches that weren’t filled. So, what have these brewers been doing with the previously labeled cans for beer that hasn’t been sold?

To make the best use of what they have in storage, some craft brewers and microbreweries have looked to converters to help them pivot to shrink sleeves and pressure-sensitive labels to cover the old label with a fresh one.

To make the best use of what they have in storage, some craft brewers and microbreweries have looked to converters to help them pivot to shrink sleeves and pressure-sensitive labels to cover the old label with a fresh one.

‘When Covid hit, we had more than one of our microbrewery customers call us up saying they needed some sleeves for cans and they needed them fast, because everything they had in vats that used to be sold to restaurants and hotels got cancelled due to shutdowns,’ says Mike Willeford, general manager of Wind Walker Label.

As of now, these methods are typically being used to salvage what was already printed and stored to maintain business in a world where unpredictable challenges continue to surface. But will this trend continue past the point where materials are easier to come by and the supply chain is stable, or will the industry roll back to the direct-to-can printing method that has been the mainstay in the brewing industry for years?

Craft brewing in the US

Though craft brewing has been around in parts of Europe for centuries, it didn’t truly exist in the United States until the late 1970s and didn’t hit its stride until the early 2000s. From 2006 to 2020, the number of craft brewers rose from 1,409 to 8,764, representing an annual growth rate of 37.28 percent, according to the Brewers Association, a not-for-profit trade association for craft brewers in the United States.

Is a craft brewer a mom+pop shop that works out of the garage, selling a few cans of beer and kegs to the local bars and markets around the neighborhood? Or is it a brewing company that works out of a warehouse with a staff of 20+ employees maintaining a few 1,000-gallon tanks and national shipment routes to liquor stores around the country? The answer is both, which is a unique problem in the US compared to Europe.

‘What the US defines as a craft brewer can be seen as a significant brewer in mainland Europe and the UK,’ said Richard Howlett, global product line leader of Accraply. ‘When we refer to a craft brewer, it’s literally a craft industry. It’s a small family company in someone’s garage. Whereas in North America, when referring to craft brewing, it’s almost literally just a brewery. It’s at a different scale.’

‘What the US defines as a craft brewer can be seen as a significant brewer in mainland Europe and the UK,’ said Richard Howlett, global product line leader of Accraply. ‘When we refer to a craft brewer, it’s literally a craft industry. It’s a small family company in someone’s garage. Whereas in North America, when referring to craft brewing, it’s almost literally just a brewery. It’s at a different scale.’

While the industry has been growing for nearly two decades, with retail sales worth 22 billion USD in 2020, not every craft brewer is seeing a high enough profit margin. A deeper dive into the numbers reveals that a majority of the 8,764 craft brewers in the United States are the small mom+pop shops. What should these craft brewers do when facing another year of disruption in the supply of blank aluminum cans?

For the foreseeable future, the answer looks to be in the labeling.

The shortage of blank aluminum cans is a serious problem which can mean the difference between whether a brewery survives past the global pandemic, or folds. Direct-to-can printing may not be an option for those who don’t have direct access to a significant supplier. As of now, the two best alternative options are shrink sleeve and pressure-sensitive labeling.

Shrink sleeves

As one of the fastest-growing label formats, shrink sleeves can provide a unique opportunity to craft brewers, as they provide full coverage of the can. But this format hasn’t historically been the first choice for many brewers.

‘Shrink sleeve has typically, at least from my experience, become a fallback for some of those medium-to-large sized breweries, who would typically be doing to direct-to-can printing,’ says Ryan Wheaton, founder of Craft Brew Creative, a branding, design and marketing company for the craft brew industry.

Even though the labeling format is growing across many markets, the term ‘fallback’ doesn’t make shrink sleeving sound too enticing for brewers. However, in comparison to direct-to-can printing, some converters believe that sleeving has more added benefits than just covering an old label. One of which is helping brand owners to stand out on shelves.

‘Because of the supply and cost issues, we’re starting to see a real high-volume acceptance of using shrink as a primary marking, even above the painted can,’ says Shane Lauterbach, president and CEO of Lauterbach Group. ‘This is partly because of all the decoration and embellishment type opportunities they can be doing for the can to draw attention to the brewers’ product on store shelves.’

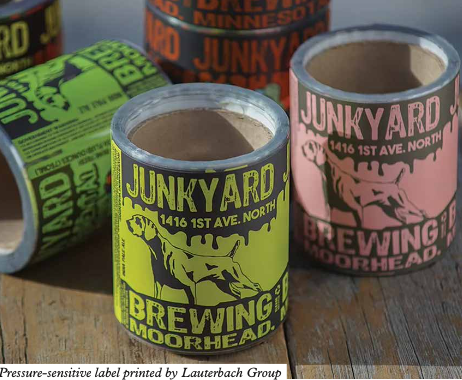

Using an HP Indigo 8000 digital press and sophisticated finishing equipment, Lauterbach is able to provide customers with embellishments such as cold foils, holographic effects, tactile varnishes, fluorescent inks, metallic inks and invisible inks. All of which are important when a product has roughly 13 seconds to stand out from the competition on the shelf in a market where competition isn’t just a handful of other companies, but thousands.

‘The sleeve gives them 360 degrees, which gives them a lot of opportunities to do marketing, like games, competitions, giveaways, and some other innovative stuff,’ says Lauterbach. He adds that these design opportunities just aren’t possible with direct-to-can labeling as it’s not as flexible as shrink sleeve and typically requires a minimum order of roughly 100,000 cans.

The flexibility of shrink sleeving is one of the reasons for its growing acceptance in the craft brew market. According to Lauterbach it gives companies a better way to manage inventory as, when blank cans become more readily available, they will no longer have to order large numbers of cans with just a single SKU. This is especially worthwhile in the craft brew industry where new flavors and SKUs are being produced on not only just a seasonal basis, but almost monthly for some.

The flexibility of shrink sleeving is one of the reasons for its growing acceptance in the craft brew market. According to Lauterbach it gives companies a better way to manage inventory as, when blank cans become more readily available, they will no longer have to order large numbers of cans with just a single SKU. This is especially worthwhile in the craft brew industry where new flavors and SKUs are being produced on not only just a seasonal basis, but almost monthly for some.

So, why hasn’t shrink sleeve become the primary form of labeling across the craft brew market?

As said earlier, with nearly 9,000 craft brewers in the United States, the market is extremely competitive. And with many brewers being individuals who are seemingly in the industry for the craft of it, procuring aluminum cans while also paying to have them sleeved can be a steep point of entry – they may not be producing enough beer to necessitate the minimum order quantity to begin with.

‘There are minimum orders on shrink sleeves of about a pallet, which is enough to cover about three to four thousand cans,’ says Wheaton. ‘So, for some of the smaller breweries, it ends up not being as cost-effective because you’re dedicated to ordering so many.’

Outside the purchase of physical sleeves and cans, the canning lines, applicators and steam or heat tunnels necessary to shrink the sleeve also necessitate a substantial capital investment before a brewer can be ready for shrink sleeve. To this Lauterbach adds that when purchasing equipment to expand into sleeving, brewers must ensure that the equipment that’s being purchased is expandable and flexible, so as not to be stuck with obsolete equipment taking up precious space on the plant floor.

Another consideration is that brewhouses need to ensure that they have an operator who knows how to handle the equipment, as shrink sleeving can be a demanding and exact process.

‘Although an aluminum can is parallel sided, it is quite challenging to achieve the high level of shrink and distortion needed to get high-quality print on the can,’ says Howlett. He adds that the capability provided by digital printing to add more complex short run graphics makes this an even more difficult process. ‘If you’re asking for one heat source or tunnel to shrink multiple different SKUs, multiple different designs, it actually needs to have a very large process window and a lot of flexibility, whereas in shrink sleeves, the more time you spend in a tunnel, the more control you have over the shrink.’

‘Although an aluminum can is parallel sided, it is quite challenging to achieve the high level of shrink and distortion needed to get high-quality print on the can,’ says Howlett. He adds that the capability provided by digital printing to add more complex short run graphics makes this an even more difficult process. ‘If you’re asking for one heat source or tunnel to shrink multiple different SKUs, multiple different designs, it actually needs to have a very large process window and a lot of flexibility, whereas in shrink sleeves, the more time you spend in a tunnel, the more control you have over the shrink.’

Though shrink sleeve does have a high initial investment, for the medium or large size brewers converters agree that it is the most logical answer to covering the direct-to-can labels. But what about the microbreweries that may not have the capital to invest in the equipment or pallets of shrink sleeves?

Pressure-sensitive labels

As the fastest-growing labeling format, pressure-sensitive labels have become the first choice for those microbreweries whose objective in becoming a brewer was not necessarily to become the next big thing, but rather just for the craft.

‘The majority of people that I’ve worked with are using pressure-sensitive labels,’ says Wheaton. ‘Just because it’s way nimbler. You can print just 1,000 labels compared to the pallet-sized orders of shrink sleeves.’

Though a cost-effective and flexible alternative to shrink sleeves, and providing a similar wrapround coverage, Willeford still sees the use of pressure-sensitive as a stepping-stone rather than the answer.

‘I always viewed the pressure-sensitive on cans as kind of a desperation measure for when companies can’t afford printed cans. They try to apply the pressure-sensitive label with the hope it goes on straight,’ says Willeford. For the most part, these companies have to apply the label after the can is filled because it wouldn’t be rigid enough otherwise.

‘I always viewed the pressure-sensitive on cans as kind of a desperation measure for when companies can’t afford printed cans. They try to apply the pressure-sensitive label with the hope it goes on straight,’ says Willeford. For the most part, these companies have to apply the label after the can is filled because it wouldn’t be rigid enough otherwise.

Another issue is durability. ‘The materials for the labels need to be durable enough to be thrown into cases, stacked up on a pallet, shipped, and be put on shelves,’ says Wheaton. ‘And then there’s the whole concept of the ice bucket challenge where if you’re using a paper label and it starts to get wet then it just peels off.’

This is one of reasons that the use of pressure-sensitive labeling has somewhat faltered, according to Willeford, although materials are available durable enough to withstand being immersed in water for a long period of time.

Another issue for self-adhesive is recyclability. Though simple and affordable, pressure-sensitive labeling affects the recyclability of the aluminum cans, which is a serious problem to craft brewers who tend to share ‘grassroot and organic’ traits along with their customers. However, there have been advancements with pressure-sensitive labels in terms of recyclability on the material providers’ side.

Another issue for self-adhesive is recyclability. Though simple and affordable, pressure-sensitive labeling affects the recyclability of the aluminum cans, which is a serious problem to craft brewers who tend to share ‘grassroot and organic’ traits along with their customers. However, there have been advancements with pressure-sensitive labels in terms of recyclability on the material providers’ side.

‘We work with the APR, MRFs and recyclers to ensure our pressure-sensitive labels do not hinder the recycling process,’ says Sarah Sanzo, compliance and sustainability manager at Avery Dennison. ‘With these insights the entire label industry is working toward the same goal thus creating a larger economy for recyclers.’

Currently, it seems that pressure-sensitive labeling isn’t catching on as well as shrink sleeving. But are these labeling methods just ways to make do in the face of the blank can shortage?

Currently, it seems that pressure-sensitive labeling isn’t catching on as well as shrink sleeving. But are these labeling methods just ways to make do in the face of the blank can shortage?

The answers vary, but the tried-and-true method of direct-to-can printing looks set to continue being the leading form of labeling when the supply chain situation returns to normal.

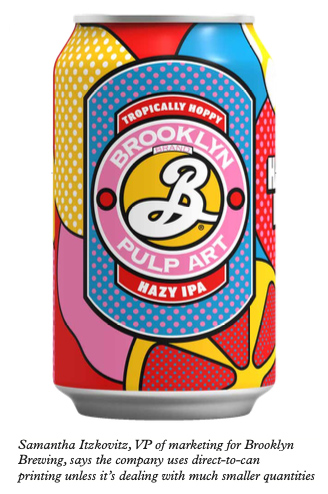

‘We run all of our cans direct-to-can unless we’re dealing with specialty or much smaller quantities,’ says Samantha Itzkovitz, vice president of marketing for Brooklyn Brewing. ‘It’s more cost-effective when producing at high quantities.’

However, there seems to be an area where shrink sleeve and pressure-sensitive labeling can take hold, and that is with the variety of SKUs and run lengths.

‘There’s still a place for shrink sleeve in this industry, and there seems to be a sweet spot where if these medium-to-large sized breweries are running enough small and medium sized runs, it makes sense to jump into sleeve,’ says Wheaton. This seems to be a shared sentiment among converters.

‘We can run SKUs as small as 5,000 for shrink sleeve and nobody is going to do a run length on a printed can that small,’ says Willeford.

Lauterbach adds that the added benefit to running these shorter SKUs and run lengths also give craft brewers flexibility. ‘In my opinion, the aluminum can shortage, just like the materials issues in the label industry, is creating an opportunity for the craft brewer to understand its inventory and capital. It’s forcing people to be better managers of their capital, and I don’t think that goes away. I think the shrink is the perfect opportunity to optimize cash flow, profitability and flexibility so that they can react to their markets and what the clients are looking for. It’s a neat opportunity for everyone involved.’

Technical features on both shrink sleeve and pressure-sensitive labeling are available through our Label Academy subscription service at www.labelsandlabeling.com/label-academy

Stay up to date

Subscribe to the free Label News newsletter and receive the latest content every week. We'll never share your email address.