Aligning leadership with business process

Business leaders often have a hard time grasping the concept of aligning the leadership function to the business processes of the company. When organizations are looking to continuously improve, it’s easy to get stuck in the silos of functions rather than processes. This roadblock to improvement is a typical phenomenon experienced in companies, including those working in labels and packaging. The best way to overcome the mental roadblock starts with an exercise of mapping the process. It can be done with traditional flow charts or value stream mapping, keeping in mind the more visual the exercise the better the input. I like to use large easel pads and handwrite the steps and encourage the area being mapped to step up and help identify problem areas. The discovery is enlightening.

I've spent many years walking the pressroom floor and designing equipment to help improve the productivity of the direct printing step. I've learned that there are many workarounds on the print room floor that are driven by upfront inconsistencies. This knowledge was important to formulating my continuous improvement assessment, leading me to start my review by examining the sales quoting and order launching process steps that are referenced as ‘pre-order’. I've discovered if there are three people in the pre-order process departments or thirteen, it is quickly discovered that everyone completes the process task a little differently. This is not an intentional action but usually the result of people having to work around some barrier in the process: a gap in the person’s training, or a lack of understanding of the downstream impact that inconsistent performance has on the operation. As part of the mapping process, I use sticky notes to highlight identified differences in the process from person to person or barriers in the process or quality issues within it. With packaging and label printers it is also amazing to learn that even after the order is received, the steps to communicate the correct data to the graphic engineers and the print shop are plagued with inconsistencies as well.

Sometimes these inconsistencies or gaps in information force the order entry group back to the customer for approvals and other information, delaying the release to the order fulfillment process by days. The order entry group has no concept that these issues impact cycle time and jeopardize achieving committed shipping dates to the customer. The consequential workarounds include shop floor expediting, added costs for purchasing expedites of raw material, air shipment to the customer, and overtime. The costliest impact is when a salesperson has to get involved with customer complaints from late shipments or has to go back to the customer because key information on the order may be missing. The loss of a salesperson’s productivity impacts future orders, revenue flow, customer relationships and competitive threats. The issues become a huge circle of rework for the enterprise.

Focus on process

A hierarchy focus on ‘functional’ areas rather than process leads to a perpetuation of the problems uncovered and a slow response to improvement. The goal of leadership driving continuous improvement is to change emphasis by implementing a focus on process and then aligning leadership to that process. When I bridge this topic with senior leaders the most compelling question raised is concerning the potential organizational structure changes. I recognize that most organizations hate the formality depicted in an organization chart. I diffuse the concern by saying that I don’t care who works for who, because the answer shakes out logically from proper process execution.

The more important question is, do leadership team members understand their responsibility as it relates to the business processes that are employed? Most organizational leaders do not think of their responsibility in this way. What matters is that there is clear and transparent communication and execution of the tasks required to complete each of the business steps and the handoff from one process step to the next is high in quality and fast in completion. The expectation for leadership is to understand the steps in the process they are responsible for and understand what happens when the process is not consistent and full of workarounds.

"I don’t care who works for who, because the answer shakes out logically from proper process execution"

A quick check of your organization's process is to review how many times the processes are completed correctly the first time. How many job packets have errors? How many datasheets from order entry are completed and correct the first time? How many times has a job stopped before it can proceed with confidence that the information is complete and correct? How often are dies put away dull, how often are plates not cleaned properly? Does an order need to be expedited because inventory was off? All of these issues cost time and are an indication of the process's first pass yield (the percentage of actions that are completed correctly the first time according to specification). You may be surprised to learn that even if a department completes its processes correctly 90 percent of the time that when you multiply all the process steps at that performance level you quickly get to a very low overall first-pass yield score. Most organizations just starting their continuous improvement focus have a process first pass yield of less than 30 percent.

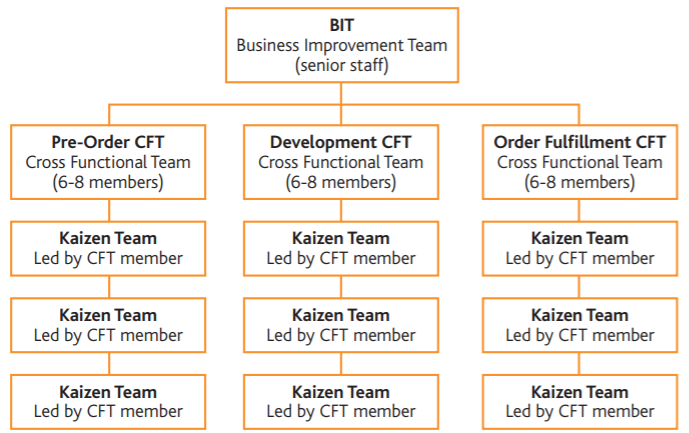

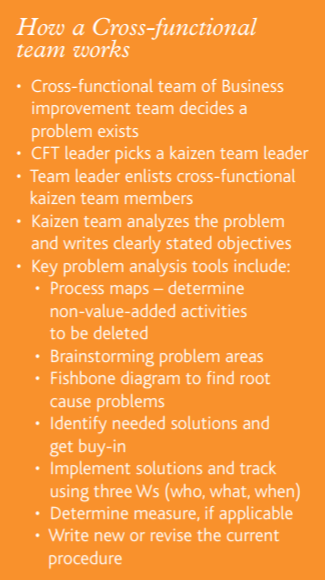

I was taught many years ago that improvement implies culture change. All organizations operate with a set of values and procedures based on the paradigms of the people who lead it. These paradigms evolve based on experiences and the environment. When change occurs, it is influenced by the people who lead the change process. To implement continuous improvement in a business, the leaders must cause the fundamental change, including how the business is managed. This change is facilitated by implementing ‘Cross-functional teams’ (CFT) for each of the major processes. The purpose of the CFT is to play a major role in improving competitiveness by identifying waste and removing barriers from the specified business processes. These barriers exist within functional areas and also between functional areas. Processes are related with each process having a supplier (input) and a customer (output) and they frequently cross-functional lines. Traditional functional silos prevent these processes from being optimized and rarely focus on the quality of the handoff. The first benefit of the CFT approach to problem-solving is that it maximizes the intellectual expertise of an organization. The power and ability of a team to solve problems and remove barriers are usually much greater than that of a single individual. Second, the cross-functional aspect of a team adds another dimension of diversity. Team members from outside a particular function generally bring objective viewpoints that can significantly impact the team's ability to arrive at creative process solutions.

Each CFT has a leader and typically high-level processes become the responsibility of an executive member of the president’s staff. The pre-order process, typically run by the VP of sales, is responsible for all process steps from customer engagement through order handoff to the operation. Product development process, typically run by the VP of engineering, is responsible for a market analysis for products and gate control of the development and product launch. Order fulfillment process, typically run by the VP of operations, is responsible for the process steps from handoff of the order to the company through shipment and ultimately collection.

The rest of the cross-functional team members come from finding the necessary process experts inside the company that understand the impact and can bring value to improving the process. The purpose of a cross-functional team member is to play a major role in helping improve global competitiveness by identifying and removing barriers from a specific business process. Using the pre-order team as an example, the most likely members would include someone from the sales organization, accounting, order entry, quoting, engineering, and the master scheduler. In a process focus structure representatives with knowledge throughout the business process bring perspective. Because the CFT is run by the appointed executive, decision points on suggested improvement can be instantaneous.

Clear goals

The key to successful CFT performance is the establishment of clear goals with a clear strategic focus. The team needs to build performance expectations that align with metrics on the production floor and are predominantly focused on cycle time, first-pass yield and productivity. The team environment gains the involvement of its members, engaging participation from all levels of the organization. An organization that has adopted the cross-functional approach is respectful of the participant's time. Meetings are held once a week for one hour. The meetings are structured to review key metrics, gather and update on kaizen (a defined improvement project with a defined start and stopping point) activity, and assign individuals to identified problems to be tackled before the next meeting. In my training, I call this a tier-three meeting because it only occurs once a week and builds on activity and support need, and brought forward from unresolved shift start-up meetings (tier-two) or daily production board reviews (tier-one).

The CFTs report into the CEO/COO. The group of CFT leaders along with the CEO, and perhaps an external expert, form the executive steering committee or Business improvement team (BIT). The Business improvement team empowers the CFTs they created to identify and remove barriers to processes that are wasteful and inhibit performance. Overall employee involvement is amplified and recognized as they quickly resolve issues with kaizen teams.

The final obstacle to managing a process-focused organization with cross-functional teams is the perception of a conflict with a traditional management structure. This obstacle is overcome when the team members realize that meetings are short and focused. Other meetings are canceled altogether. The CFT meetings are scheduled and designed to respect a person’s time, focus on key metrics and celebrate success. Each meeting ends with meeting minutes and defined actions. Individuals are happier with focus, recognized results, and the fact that their team completes tasks quickly. The cross-functional team becomes the driver to cultural changes focused on operational excellence that brings geometric improvement to performance.

Stay up to date

Subscribe to the free Label News newsletter and receive the latest content every week. We'll never share your email address.