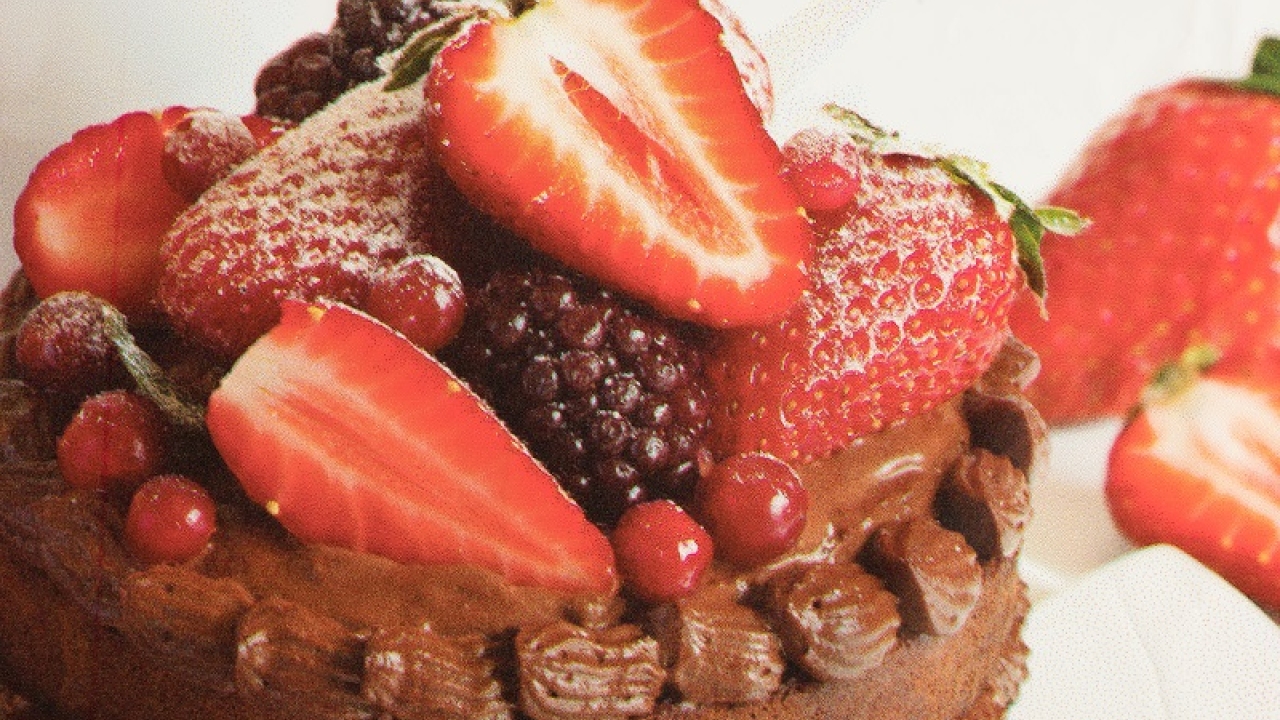

Cake making for flexo

Compare the current print process for flexible labels and packaging with ‘The Great Global Bake Off’, where many chefs compete by using their own ‘magic’ ingredients to bake the perfect cake.

Such a scenario is the antithesis of the reality in a factory that produces thousands of cakes every day; cakes which consistently and reliably look and taste the same. The factory’s recipe determines the types and quantities of the ingredients and defines the sequence and method for adding each to the mix to achieve the desired result.

Baking a great cake requires more than just the right ingredients, there’s an element of control required in the process; the oven has to be at the right temperature, the mixture has to be baked for the right amount of time and the cooked cake must be left to cool before adding the decorations or filling needed to produce the perfect cake. The factory expects standard results by repeating its process day in, day out and achieves the same result every time with no surprises or disappointments.

With flexo printing, the production of consistent output has historically been challenging. Because there are so many ‘ingredients’ in the flexographic print recipe – tapes, plates, aniloxes, inks and substrates, as well as many cooks and chefs – it has always been difficult to achieve consistency in the final output.

A brand with a global presence must print using many different printers in different countries, possibly even on different substrates. The brand owner produces designs which are sent to a version one file designer to convert into a workable format for the next step. Repro shops then sit between the brand owners and the printers adding to the artwork and RIPing the files to make plates. It sounds simple, doesn’t it? A print recipe might appear simple but when the repro shop tells the brand, ‘You can’t print this artwork, it has problems; this needs to change, that needs to go’, then following that recipe suddenly becomes tricky. Pre-press procedures often identify all sorts of previously unseen problems such as files which fail to include embedded images, background tints added to compensate for not fading properly to zero, reverse text, illegible small tinted text, serifs on fonts and split colors. Such matters pose technical difficulties from platemaking to printing and can negatively affect the image fidelity of the printed label or packaging. Where spot colors are used they can become an extra cost since they require other inks, extra plates and additional wash-ups which, in turn, cause press downtime. Repro shops act as go-betweens for the brands, or packers and the printers, and frequently have to educate the designers about the limitations they need to work with in order to achieve high-quality consistent flexographic print.

Printers are given color and density targets by the brands but, beyond that, all printers will have their own unique mix of ingredients. They are all constrained by tight budgets too so that, most of the time, they work with trusted incumbents who juggle all the ingredients in ways that ‘just work’ and this is the ‘Great Global Flexo Print Problem’.

The result is inconsistency in the final printed product. We consulted with a well-known global brand who told us about a consistency project they had undertaken. It involved gathering packaging for a particular product line that had been produced in different locations and checking the color consistency across the samples. Their results? Typical of flexo printed material, the brand’s color varied hugely from one batch to another.

What needs to change?

There are numerous problems encountered by the flexo industry but a holistic approach to solving all of them is unrealistic because there are too many contributors to the overall process, all of whom have their own goals which mean they are unlikely to yield to an approach which could damage their competitive advantage. A tactical approach appears more achievable; by educating the designers so that they understand the limitations and capabilities of flexography it should be possible to achieve more consistent output even in the face of competition from the offset, gravure and digital printers who do not face the same challenges. Sadly, probably because it’s been around the longest, flexo has a reputation as the poor cousin of offset and gravure.

Educating designers is a worthy aspiration but will take time and money and there’s no guarantee of success but flexo needs a radical change in perception to move away from the traditional thinking. By reducing the variability of the pre-press and print process, most artwork and design headaches can be eradicated. Developments such as the technology embedded in Bellissima DMS achieves this reduction with one screen, one anilox and two plates, and also makes possible consistency across jobs, substrates, countries and printers. In this new world, where tighter controls are superfluous and where global support is available from key suppliers, we will surely see this theory maturing into our reality.

This opinion article was first published in Labels & Labeling issue 4, 2018

Stay up to date

Subscribe to the free Label News newsletter and receive the latest content every week. We'll never share your email address.