Climate change. Can we make a difference?

Hardly a day goes by without the media carrying some news or feature article about extreme weather conditions. Hurricanes, storms, floods, drought, heat, cold ̶ often claimed to be the worst, highest, lowest, driest, wettest, etc, ever known ̶ and all placed at the door of climate change and global warming. In turn largely attributed to consumption of fossil fuels, deforestation, carbon emissions and air pollution.

While it is true that extreme weather conditions can be traced back and compared over the years since detailed weather and temperature reports first started to be collected in the 1880s, it can also be relevant to additionally look at newspaper archive records going back to the early 1700s to see whether such extreme conditions were reported up to 180 or more years prior to the official detailed records began.

Let's take drought conditions. A newspaper report from March 1740 stated that there had been a severe drought in Spain which had continued for nearly two years, while in August 1748, news from Warsaw reported that the country was so devastated by drought and grasshoppers that people were leaving to avoid perishing by famine. Yet drought in Europe is currently claimed to be a phenomenon that has only been happening over the last 50 years.

What about hurricanes and storms? How do they compare with 300 years ago?

In 1703 the ‘Great Storm’ is said to stand alone in history, making itself felt all over Europe. Houses were tossed about like houses of cards, and caused many tragedies. June 1725 sees reports from Bohemia that read, ‘There was such a storm at Prague that the like had not be seen in the memory of man, hail stones having fallen there, some of which weighed a pound and three quarters [0.78kg].’

In terms of extreme stormy weather we can also look back to a report from the Netherlands in January 1735 when a major storm and excessive flooding left wrecks and dead bodies on the coast of Flanders. A further report from England refers to a violent storm of hail ‘as big as pigeon's eggs, some two or three inches long [5-8cm], which tore up the corn and taken off every grain. The hail broke people's heads and killed partridges, hares, plovers and pigeons in the fields.’

A report from Amsterdam in January 1740 mentions storms had played havoc at sea, and that the cold temperatures in the country were so rigorous that people had been frozen to death. Some that were skating from one town to another had been found starved.

October 1780 saw what was claimed as one of the greatest storms that has ever occurred. Starting in mid-Atlantic, it was first felt in the Barbados, where trees and houses were blown down. At Martinique some 9,000 persons perished, and 1,000 at St Pierre, where not a house was left standing. St Domingo, St Vincent, St Eustache, and Port Rico were next visited and devastated. At Port Royal the cathedral, seven churches, and 1,400 houses were blown down.

At the Bermudas fifty British ships were driven ashore and 22,000 persons perished. The report noted that when day broke the country looked as if had been blasted by fire; not a leaf, scarcely even a branch, remained upon the trees.

All sounds little different to the powerful storm and hurricane named Dorian that tore off roofs, caused severe flooding, led to many deaths, and flattened much of the Bahamas in early September 2019 – some 237 years later.

Storms, thunder, lightning, hail and rain, with hurricanes and tempests being frequent and fatal throughout France, were reported during June and July 1787. Fields were said to be left completely defoliated and houses thrown down, men and cattle were grievously wounded and birds of all kinds killed. Reports stated that hailstones were of an irregular form, many of them equal in size to a man's fist.

Extremes of cold also appear frequently in newspaper reports from the 1700s. In January 1716 reports from Amsterdam said that nothing could be seen but ice extending 4 or 5 leagues (15 to 20km) out into the North Sea. During the same extreme cold the River Thames was quite frozen over.

February 1727 sees reports that say parts of the Baltic Sea were completely frozen, while In March 1736 the sea was frozen over and it was possible to walk on the ice from Denmark to Sweden.

In southern England the most severe frosts were reported in January 1740, with ice floating free in the English Channel and reports of several thousands of people walking and skating over ice on the River Thames. A further report from 1740 said that the Seine in Paris was so frozen up that there was no possibility of getting fresh water.

A report from North America in June 1742 talks of large islands of ice floating southwards in the approaches to the entrance of the Churchill River. Some of these ice islands were said to be up to 50 fathoms (around 90 meters) above the water, and three times that under the water. At the same time, thick fogs were noted as suddenly appearing.

The interesting thing about all these reports (and there are hundreds more that can be cited) of extreme weather conditions, many as bad if not more severe than those being reported today, is that they were all occurring long before the industrial revolution commenced, long before fossil fuels (coal, natural gas and oil) were being extensively burned or turned into plastics, long before deforestation, long before carbon emissions and greenhouse gases became problematic and before air pollution was being recorded. It is therefore difficult to solely blame fossil fuel usage or deforestation for the extreme weather conditions that we now experience today.

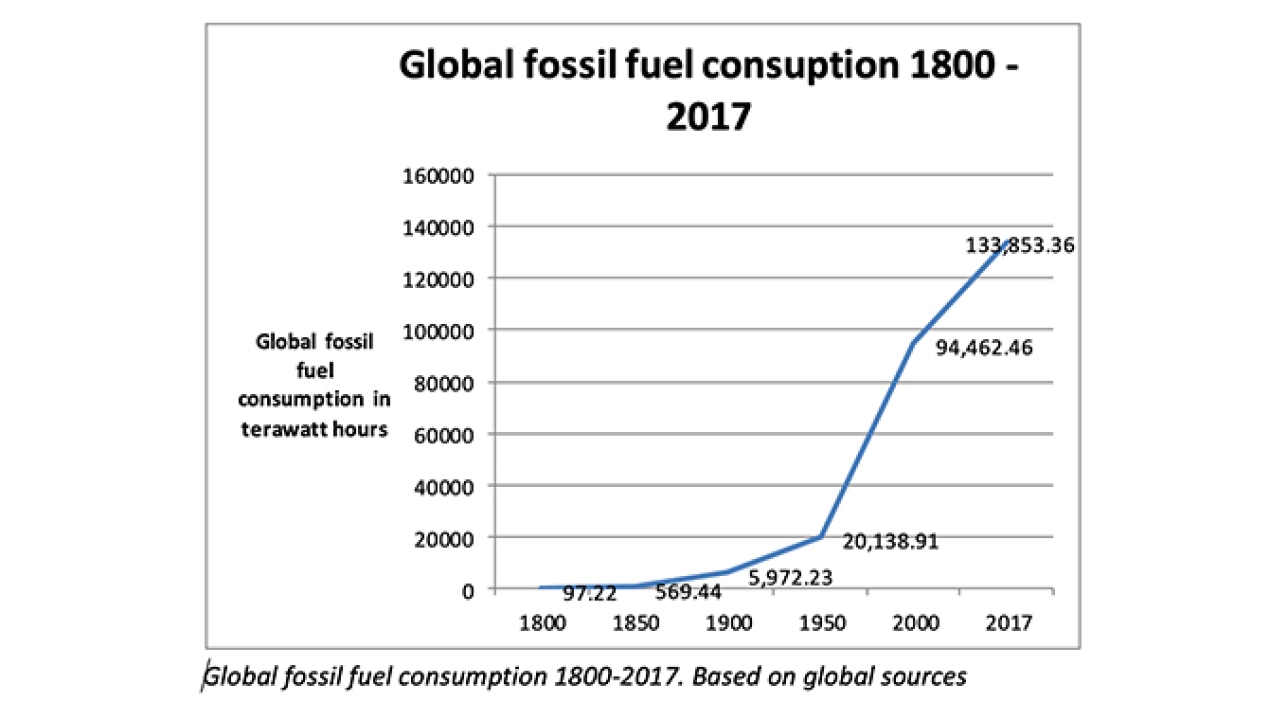

To look at when and how fossil fuels began to have an impact it is necessary to study Figure 1. Certainly, fossil fuel energy was a fundamental driver of the industrial revolution, and the technological, social, economic and development progress which has followed. Energy has undoubtedly played a strongly positive role in global change but, as we have been seeing since the mid-1900s (long after the industrial revolution), it does now appear to have negative impacts contributing to global rises in temperature, and there is an ever-growing need to reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

The paper, plastics, label and packaging industries still need to do much more to reduce the use of fossil fuels, to cut energy consumption in their plants and distribution systems, and to look more at solar, wind and other renewable energy sources wherever possible.

While extreme weather patterns were occurring long before widespread fossil fuel usage, historical records from the 1700s and 1800s certainly do appear to confirm that the world is steadily slowly getting warmer. Extremes of frost and ice, rivers and seas freezing over, over sized hailstones, etc, all seem to be much less today than in the 1700s. Escalating fossil fuel usage undoubtedly appears to have had a key role to play in global warming in recent years, but other factors are equally as important ̶̶ such as deforestation and population growth.

Generally recognized is that the greenhouse effect on earth has been increased because of deforestation. Something like 20 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions on earth today are said to be caused by tropical deforestation (much of it by burning), contributing to desertification, global warming, wildlife extinction and population displacement. Indeed, around half of the world's tropical forests are now said to have been cleared. The global chart for rising deforestation probably looks very similar to that for fossil fuels.

Where do all the cut down trees end up? Figures from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) indicate that globally around 40 percent of the annual industrial wood harvest is processed for paper and paperboard. Although that is a huge proportion, the great majority of the trees used for pulp and paper in the world actually come from plantation-grown wood – fast-growing wood with harvesting cycles ranging between five and 20 years – and not from the destruction of tropical forests. The industry uses fast growing and well-managed plantations.

Indeed many countries now plant more trees than they actually harvest. Scotland now has more woodland than at any time since the 14th century; Canada has many policies and laws to commit to sustainable forest management; reforestation is required as part of the federal forest law in Germany; in Finland, many of the forests are managed by the wood products and the pulp and paper industry; extensive replanting programs have existed in China since the 1970s and their forest cover is increasing.

Interestingly, a recent study published in Science stated that global tree restoration has the potential of erasing nearly 100 years of carbon emissions. Indeed, is probably the best (if not the only) climate change solution available today.

Maybe the label industry could commit to doing more in terms of tree restoration. After all, it is a major paper user. If every label converter and industry supplier committed to planting, say, 50 or more trees each year (or a least funding them through one of the global tree planting schemes, or establish a dedicated label industry tree planting scheme) it would be a major and positive industry commitment.

Members of Mossy Earth for example, commit to planting 24 trees every year to counter deforestation and become carbon neutral, while the Woodland Trust will even supply tree saplings free of charge. So why not a label industry reforestation scheme?

It’s true that the paper (and label) industry – as already mentioned – has no need to be a cause of natural forest degradation, or deforestation. Through proper management with independently certified forestry standards, such as FSC and SFI, and through continuing improvements in recycling, the supply of paper for labels and packaging should remain responsible for many years to come. But it could still be a positive initiative to further support reforestation.

One other key factor in global warming and climate change is population growth. This has mainly been occurring in emerging countries, although it has to be said that population decline is starting to become a growing factor in many developed countries

It is difficult to see what the label and packaging industry can do to mitigate the effects of population growth. Indeed, population growth has been a major positive contributor in the expansion and globalization of these industries, particularly from the late 1900s, and will probably continue to do so.

However, reducing the use of fossil fuels, cutting back on deforestation and tree planting on their own are unlikely to completely solve the problems of global warming all the time that the global population is still dramatically rising. Growing populations need to be fed and housed; they need water; they need homes; they need transport and energy. Undoubtedly more will need to be done in the coming years to feed the world’s populations. The packaging and label industry needs to contribute to this future requirement in the most sustainable and environmentally friendly way possible.

What can definitely be said is that the world’s populations have largely become too much of a throw-away society (food, clothing, toys, packaging, gadgets, etc), too free with its energy usage, too little interested in enhanced conservation, re-usage and recycling. We all need to change, and maybe the label industry could do more to be seen to lead the way in many of these areas. There is undoubtedly still considerable potential for new opportunities and solutions.

Hopefully it is still not too late for everyone to play their part in a more sustainable future?

Stay up to date

Subscribe to the free Label News newsletter and receive the latest content every week. We'll never share your email address.